By Dr. Layne Garrett, Au.D., FAAA, ABAC, CH-TM, CDP (About | YouTube | Podcast | LinkedIn)

Date Published: February 5, 2026 at 9:00 AM

Hearing loss is strongly linked to changes in brain function, cognitive load, social engagement, and fall risk. Research shows that untreated hearing loss increases listening effort, accelerates social withdrawal, and is associated with higher rates of cognitive decline and dementia. The 2024 Lancet Commission identified hearing loss as one of the largest potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia at the population level in midlife. However, current evidence does not prove that treating hearing loss prevents dementia for everyone. What treatment does reliably improve is daily cognitive function, listening effort, social participation, and quality of life. For these reasons, addressing hearing loss early is widely considered part of a comprehensive brain-health strategy.

TL;DR

Hearing loss affects brain function, social engagement, fall risk, and overall health in measurable ways. Research shows strong associations between hearing loss and cognitive decline, though we cannot yet prove that treating hearing loss prevents dementia. What we can say: addressing hearing loss early reduces cognitive load, supports social connection, improves safety, and enhances quality of life right now—benefits that matter regardless of long-term dementia outcomes.

⚠️ Important Medical Information

Seek immediate medical attention if you experience:

- Sudden hearing loss in one or both ears

- Hearing loss with severe dizziness or vertigo

- Hearing loss with severe headache or neurological symptoms

- Rapid cognitive decline or confusion

These symptoms require urgent evaluation by a physician or emergency department. This page addresses gradual hearing loss and cognitive health connections, not emergency situations.

Key Takeaways

- The 2024 Lancet Commission's population-level models indicate that hearing loss in midlife contributes one of the largest potentially modifiable shares of dementia risk at the population level.

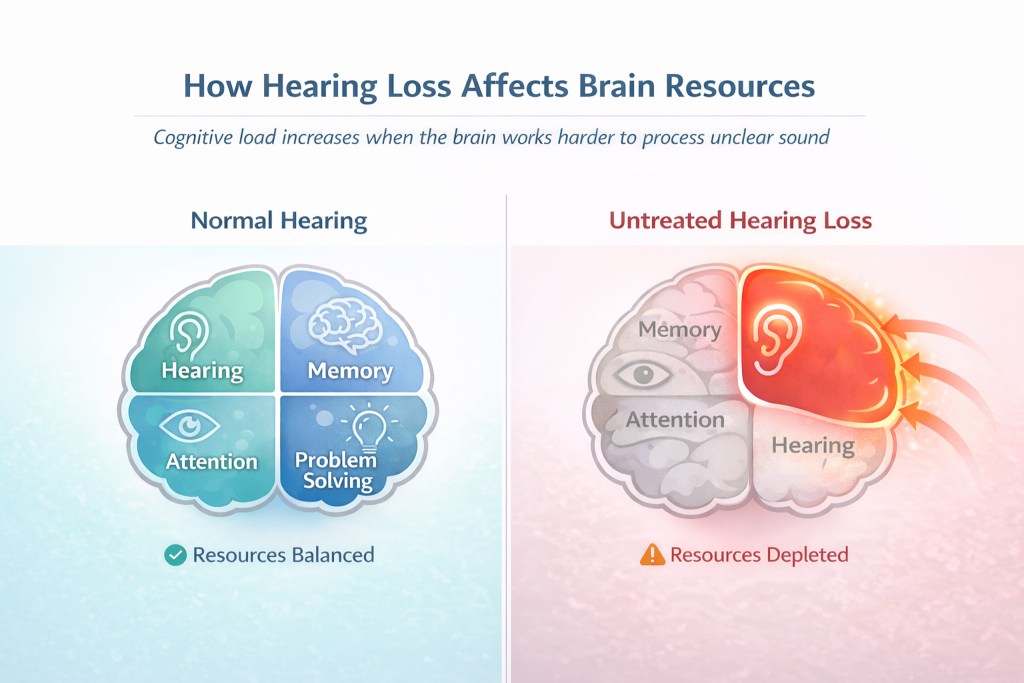

- Untreated hearing loss increases cognitive load, meaning the brain must work harder to process unclear sound, diverting mental resources from memory and attention.

- Long-term hearing loss leads to measurable brain reorganization (auditory deprivation), where auditory processing regions may be recruited for non-auditory tasks.

- Hearing loss significantly increases fall risk and balance problems, even when controlling for other age-related factors.

- We cannot yet say that hearing aids prevent dementia, but early intervention may support cognitive health through reduced listening effort and maintained social connection.

Who This Page Is For

This comprehensive guide is designed for:

- Adults concerned about memory and cognition who recently learned they have hearing loss and want to understand the connection

- Family members watching a loved one experience both hearing difficulty and cognitive changes, wondering if they're related

- Proactive individuals researching whether treating hearing loss might help preserve brain function and overall health as they age

- People who passed a hearing test but still struggle with understanding speech, especially in noisy places, and wonder if this affects cognitive function

- Anyone considering hearing aids who wants to understand the broader health implications beyond just hearing better

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Why Hearing and Brain Health Are Connected

- How Hearing Loss Affects Your Brain

- The Research on Hearing Loss and Dementia

- Beyond Cognition: Other Health Impacts of Untreated Hearing Loss

- Who Is Most at Risk?

- The Case for Early Intervention

- What to Do If You're Concerned

- If You're Worried About Memory: The Simplest Next Step

- What Researchers Agree On vs What's Still Being Studied

- Common Myths About Hearing Loss and Cognition

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Related Topics

- References & Key Studies

- About Timpanogos Hearing & Tinnitus

Introduction: Why Hearing and Brain Health Are Connected

Over the past few years, I've noticed something. More patients come in worried not just about missing conversations at dinner, but about their memory. They ask: "Could my hearing loss be affecting my brain?" "Is this going to lead to dementia?" "Will hearing aids help my memory?"

These are important questions. They deserve honest, evidence-based answers—not marketing claims or false reassurance.

The relationship between hearing loss and cognitive health is real, measurable, and significant. Study after study has found connections between hearing difficulty and cognitive decline, dementia risk, depression, and even physical problems like falls. The 2024 Lancet Commission on dementia prevention analyzed population-level models showing that hearing loss in midlife contributes one of the largest potentially modifiable shares of dementia risk.

But here's what I want to be clear about from the start: association doesn't prove causation. We don't yet have definitive proof that treating hearing loss prevents dementia. What we do have is compelling evidence that hearing loss affects how your brain functions, how you engage socially, and how you move through the world. These factors matter for long-term cognitive and physical health.

In this guide, I'll walk you through what we actually know from research, what remains uncertain, and why I still strongly recommend addressing hearing loss early even though we can't make promises about preventing dementia. We'll look at the mechanisms connecting hearing and cognition, the latest research findings, and what early intervention might mean for your brain health.

If you want to explore more about how improving hearing can support overall brain health, I've written about this connection in detail in my post on Better Hearing, Better Brain, Better Life.

CLINICIAN'S NOTE: Over 20+ years, I've watched countless patients wait years to address hearing loss. What strikes me most isn't just how they struggle to hear—it's the cognitive exhaustion they describe. They talk about feeling mentally drained after social events. They avoid situations that used to energize them. They feel like their mind isn't as sharp as it used to be. When we successfully treat their hearing loss, many describe feeling mentally clearer and less fatigued. That's not a cure for dementia. But it's real improvement in daily cognitive function.

This page will help you understand the science, make informed decisions, and know what questions to ask your healthcare providers. Whether you're experiencing hearing loss yourself or supporting someone who is, understanding these connections is an important step toward comprehensive health management.

How Hearing Loss Affects Your Brain

When most people think about hearing loss, they imagine it as simply a volume problem. Like turning down the radio. But hearing loss actually changes how your brain functions in profound and measurable ways. Let's look at the four major mechanisms researchers have identified.

How Does Hearing Loss Increase Cognitive Load?

Imagine trying to have a conversation at a restaurant while simultaneously solving math problems in your head. That's essentially what your brain does when you have hearing loss. This phenomenon is called increased cognitive load. It's one of the most well-established connections between hearing difficulty and cognitive function.

Here's how it works: When sound reaches your ears clearly, your brain can process speech relatively effortlessly. You hear the words. You understand the meaning. You remember what was said. You formulate a response. All without thinking about it. But when hearing is impaired, your brain has to work much harder just to figure out what words are being said.

Research on effortful listening, particularly work by Dr. M. Kathleen Pichora-Fuller and colleagues, has shown that this extra effort comes at a cost. When your brain dedicates more resources to basic speech recognition, it has fewer resources available for higher-level tasks like:

- Understanding the meaning and context of what's being said

- Storing information in memory

- Making connections between new information and what you already know

- Planning your response and participating actively in conversation

This isn't theoretical. Studies using brain imaging and cognitive testing have documented that people with hearing loss show different patterns of brain activity during listening tasks compared to people with normal hearing. They're recruiting additional brain regions—areas normally used for other cognitive tasks—just to understand speech.

The real-world impact is significant. Patients describe feeling mentally exhausted after social events, even when they didn't do much physical activity. They need more recovery time after meetings or gatherings. Some notice their memory seems worse in the afternoon or evening when they're mentally fatigued from a full day of effortful listening.

CLINICIAN'S NOTE: One of the most common things I hear from patients after they've adjusted to well-fitted hearing aids is: "I didn't realize how tired I was all the time." They describe having energy left at the end of the day. They can stay engaged in evening conversations with family. They don't need to retreat to quiet spaces as often. The cognitive load reduction is real and noticeable.

What Is Auditory Deprivation and Brain Reorganization?

Your brain is remarkably plastic. It changes and adapts throughout your life based on how you use it. This is generally a good thing. But it creates a problem when your ears stop delivering clear auditory information. The phenomenon is called auditory deprivation. It's one of the more concerning long-term effects of untreated hearing loss.

When your brain consistently receives degraded or absent sound signals from your ears, it doesn't just sit there waiting. It reorganizes. Research using brain imaging techniques has documented these changes. Studies show that with long-term hearing loss, regions of the brain that should respond to sound instead show increased activity during visual tasks. The brain is essentially adapting its processing resources based on the input it's receiving.

This reorganization creates several problems. First, it may make it harder for your brain to process sound effectively even when hearing is improved with hearing aids or cochlear implants. Patients who have had hearing loss for many years often need more time to adjust to amplification. Their brain has to "relearn" how to process auditory information efficiently.

Second, there's emerging evidence that this reorganization might be part of the mechanism linking hearing loss to cognitive decline. When brain regions reorganize away from their original purpose, it may affect overall cognitive efficiency and reserve. That's the brain's ability to cope with age-related changes or pathology.

The critical question many people ask is: Is this reversible? Research suggests the brain can adapt again when hearing is restored. But the process takes time. It's more challenging the longer hearing loss has gone untreated. Earlier treatment may make adaptation easier, though the optimal timing window is still being clarified by ongoing research.

How Does Hearing Loss Lead to Social Isolation?

Humans are social creatures. Our cognitive health is intimately tied to social engagement, meaningful relationships, and active participation in our communities. This is where hearing loss creates what I call a cascade effect. One problem leads to another, which leads to another, creating compounding impacts on brain health.

Here's how the cascade typically unfolds: First, hearing difficulty makes conversations more challenging, especially in noisy environments like restaurants, family gatherings, or community events. You find yourself asking people to repeat things more often. You miss jokes or lose track of conversations when multiple people are talking. Social interactions that used to be enjoyable become work.

Second, many people begin to withdraw. It's not usually a conscious decision. You might turn down invitations because you're tired, or you know the venue will be too noisy. You might participate less in conversations because you're not confident you'll understand everything. You might avoid phone calls or group situations. This gradual withdrawal is extremely common and completely understandable.

Third, this reduced social engagement starts to affect both mental and cognitive health. Research has consistently shown that social isolation and loneliness are independent risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia. There's also strong evidence linking social isolation to depression and anxiety in people with hearing loss.

The mechanisms are complex and interconnected. Social engagement provides cognitive stimulation. You're processing complex conversations, dealing with unexpected topics, managing social dynamics, and staying mentally active. Social connection also tends to encourage other healthy behaviors like physical activity and engagement in hobbies or volunteer work. And social relationships provide emotional support that protects against depression and anxiety.

When hearing difficulty reduces social engagement, all of these protective factors diminish. Research suggests this social pathway may be one of the most important connections between hearing loss and cognitive decline. It's not just about the hearing itself. It's about how hearing difficulty changes your behavior and social world in ways that affect your brain.

CLINICIAN'S NOTE: What I see constantly is this cascade—but I also see it reverse. When patients get properly fitted hearing aids and stick with them through the adjustment period, they start accepting invitations again. They join groups they had stopped attending. Family members tell me their loved one is "back." More engaged. More like themselves. This reversal of social withdrawal isn't a guarantee against cognitive decline. But it's meaningful for quality of life and probably for long-term brain health.

Is Hearing Loss Linked to Balance Problems and Falls?

The connection between hearing loss and balance problems surprises many people. Your ears aren't just for hearing. They're also crucial for balance through the vestibular system. But even beyond the direct vestibular contribution, your ability to hear actually helps you maintain stability and spatial awareness.

Here's what research has shown: People with hearing loss have a significantly higher risk of falls compared to those with normal hearing. Studies by Dr. Frank Lin at Johns Hopkins found that even mild hearing loss is associated with a nearly threefold increased risk of falls. The risk increases with severity of hearing loss.

But why does hearing affect balance? There are several mechanisms at work. First, sound provides important environmental cues that your brain uses for spatial orientation. You unconsciously use sound to monitor your environment. You hear traffic, footsteps, environmental echoes that help you understand the space around you. When this auditory information is reduced, you lose some of that spatial awareness.

Second, there's the cognitive load issue again. Walking, especially on uneven surfaces or in crowded areas, requires cognitive resources for balance control and navigation. When your brain is already working hard to process degraded auditory input, it has fewer resources available for balance and gait control. Research has shown that cognitive dual-tasking—doing two cognitively demanding things at once—impairs balance, particularly in older adults.

Third, there may be shared underlying pathology. The inner ear contains both the hearing organs (cochlea) and balance organs (vestibular system). Conditions that damage one may affect the other. Additionally, factors like reduced blood flow, inflammation, or age-related changes might impact both hearing and balance systems simultaneously.

The fall risk is not trivial. Falls are a leading cause of injury, hospitalization, and mortality in older adults. A fall can mark a turning point in independence and quality of life. Multiple studies have found that older adults with hearing loss are more likely to be hospitalized for fall-related injuries.

The encouraging news is that there's some evidence that treating hearing loss might reduce fall risk, though more research is needed. The proposed mechanism is that by reducing cognitive load and improving spatial awareness through sound, hearing aids might help free up cognitive resources for balance control.

The Research on Hearing Loss and Dementia

This is the section where I need to be especially careful to separate what we know from what we hope or suspect. The relationship between hearing loss and dementia risk is one of the most important areas of research in both audiology and neurology right now. Let me walk you through what the evidence actually shows.

What Did the 2024 Lancet Commission Find?

In 2024, the Lancet Commission updated its influential report on dementia prevention, intervention, and care. This comprehensive review by international experts identified 14 modifiable risk factors across the lifespan that contribute to dementia risk.

In the Commission's population-level models, hearing loss in midlife contributes one of the largest potentially modifiable shares of dementia risk. This is a significant finding that has received considerable attention in both medical literature and popular media.

But here's what this finding actually means, and what it doesn't mean. The Commission used population attributable fraction modeling—a statistical approach that estimates what percentage of cases in a population might theoretically be linked to specific risk factors if those relationships are causal. The estimates come from observational studies, not randomized controlled trials, and the specific percentages vary depending on which models and datasets are used.

The Commission is not saying that hearing loss directly causes a specific percentage of dementia cases, or that any individual person can reduce their personal dementia risk by a calculable amount by treating hearing loss. They're saying that hearing loss in midlife is associated with increased dementia risk later in life, and because hearing loss is both common and potentially modifiable, it represents an important target for prevention efforts at the population level.

This distinction matters. For an individual person, we cannot say, "If you treat your hearing loss, you will reduce your personal dementia risk by X percent." The relationship is more complex than that. It involves multiple mechanisms and many other factors.

What we can say is that maintaining good hearing throughout life appears to be important for brain health. Addressing hearing loss is part of a comprehensive approach to potentially supporting cognitive function as we age.

What Do Long-Term Studies Show About Hearing Loss and Dementia?

EVIDENCE REVIEW STATEMENT: This section is reviewed every 6 months to incorporate new research findings as they become available. Major studies and updated analyses are added to ensure this information reflects current scientific understanding. Last review: February 2026.

The association between hearing loss and cognitive decline didn't emerge from a single study. Multiple long-term studies show that hearing loss is associated with faster cognitive decline. Let me highlight some of the key research that has shaped our understanding.

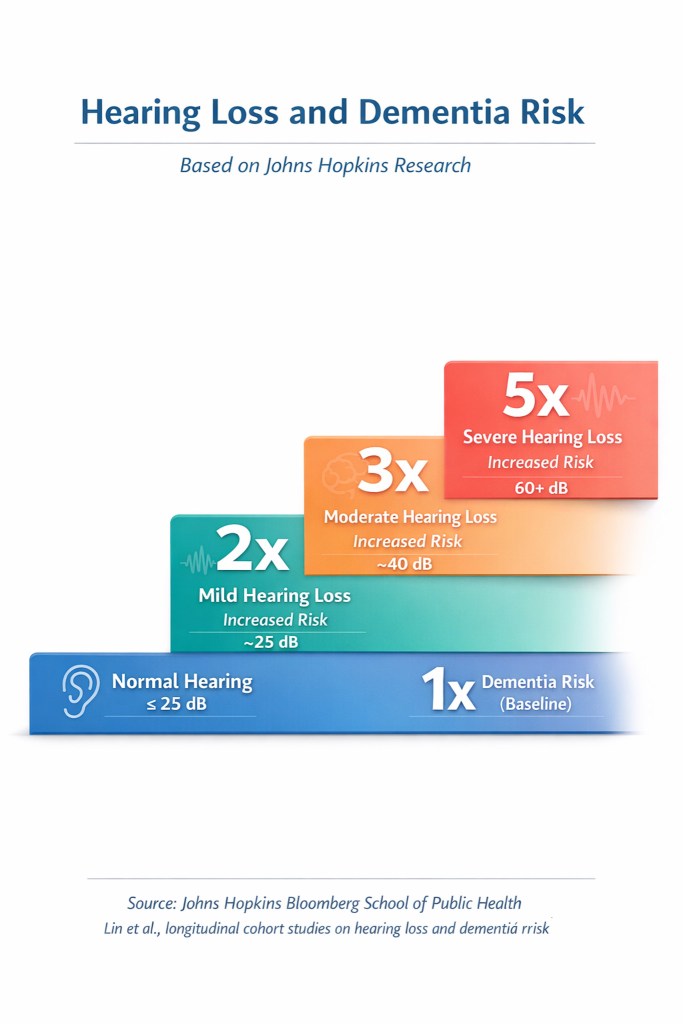

Dr. Frank Lin and colleagues at Johns Hopkins published an influential 2011 study in Archives of Neurology (now JAMA Neurology). They followed nearly 640 adults for up to 18 years. They found that people with hearing loss had accelerated rates of cognitive decline compared to those with normal hearing. The rate of decline increased with severity of hearing loss. Those with mild, moderate, and severe hearing loss had 2-, 3-, and 5-fold increased risk respectively of developing dementia over the study period.

A 2013 study by Lin and colleagues, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, followed nearly 2,000 older adults for an average of 11 years. They found that hearing loss was independently associated with incident dementia. Importantly, this association remained even after controlling for other risk factors like age, diabetes, smoking, and cardiovascular disease.

Research from other groups has produced similar findings. The Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study followed thousands of adults and found associations between hearing loss and cognitive function. Studies in Europe, including the UK Biobank data and other population cohorts, have documented similar relationships.

A critical aspect of these studies is their longitudinal design. They follow people over time rather than just looking at a single point. This strengthens the evidence because it shows that hearing loss precedes cognitive decline, not just that the two occur together.

However, these are still observational studies. They show association, not causation. People with hearing loss might differ from people without hearing loss in other ways that affect dementia risk. This is where randomized controlled trials become important, which leads us to the next section.

Does Hearing Loss Actually Cause Cognitive Decline?

The observational research creates a compelling case for a relationship between hearing loss and cognitive decline. But proving causation—that hearing loss actually contributes to cognitive decline, rather than just being associated with it—is much more difficult.

There are three main theories about why hearing loss and cognitive decline occur together. First is the causal hypothesis: hearing loss actually contributes to cognitive decline through mechanisms like cognitive load, auditory deprivation, and social isolation that I described earlier. This is the most hopeful hypothesis because it suggests that treating hearing loss might reduce dementia risk.

Second is the common cause hypothesis: some underlying factor affects both hearing and cognition. For example, vascular disease, inflammation, or other age-related processes might damage both the auditory system and brain structures important for cognition. If this is the main explanation, treating hearing loss might not affect dementia risk because the underlying cause would still be present.

Third is reverse causation: early cognitive decline might cause people to struggle with hearing situations even when their hearing is technically normal. We know that processing complex auditory information requires intact cognitive function. So very early cognitive changes might manifest as hearing difficulty.

The reality is probably some combination of all three. Some hearing loss may be caused by processes that also affect the brain. Some cognitive difficulty might make hearing problems seem worse. And some of the impact of hearing loss on cognition is probably direct through mechanisms like increased cognitive load and reduced social engagement.

This is where randomized controlled trials become crucial. In a proper RCT, you randomly assign people to receive hearing treatment or not. Then follow them to see if the treated group has better cognitive outcomes. This design helps rule out confounding factors and establish causation more definitively.

CLINICIAN'S NOTE: When patients ask, "Is my hearing loss going to give me dementia?" I tell them we don't know for certain that treating hearing loss prevents dementia. But I also explain that hearing loss affects daily cognitive function, social engagement, and quality of life in ways that are measurable and meaningful right now. Even if we can't promise dementia prevention, addressing hearing loss makes sense for your current cognitive function and overall wellbeing. That's reason enough to act.

Can Hearing Aids Prevent Dementia?

This is the question I get asked most often. It deserves a direct answer: We don't know yet. We have suggestive evidence, but we don't have definitive proof that hearing aids prevent or delay dementia.

Let me explain what evidence we do have. Several observational studies have found that hearing aid users appear to have lower rates of cognitive decline compared to non-users with similar hearing loss. A 2018 study published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society found that among people with hearing loss, hearing aid use was associated with better cognitive performance and delayed cognitive decline.

However, observational studies of hearing aid use face a major problem: selection bias. People who get hearing aids might differ from those who don't in ways that also affect cognitive outcomes. They might be more proactive about their health. Have better access to healthcare. Have more social support. Or have different baseline cognitive status. These differences, rather than the hearing aids themselves, could explain better cognitive outcomes.

This is why the ACHIEVE trial (Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders) was so important. ACHIEVE was a randomized controlled trial that followed nearly 1,000 older adults for three years. Participants were randomly assigned to either receive hearing intervention (hearing aids plus audiology support) or a health education control group.

The primary results, published in The Lancet in 2023, showed no significant effect of the hearing intervention on cognitive change over three years in the full study population. However, in a prespecified subgroup analysis of participants from the ARIC cohort—a group at higher baseline risk for cognitive decline—the hearing intervention was associated with a 48% reduction in cognitive decline over three years.

What do we make of these findings? The ACHIEVE study was landmark research, but it has limitations. The participants had relatively mild hearing loss on average. Most were cognitively healthy at baseline. The intervention period was three years—potentially not long enough to see effects on dementia risk, which may take decades to develop. And the subgroup finding, while promising, wasn't the primary outcome and needs to be confirmed in future studies.

Several other large trials are ongoing or planned, including the CLARITY trial in the UK. These studies will help us better understand whether and for whom hearing intervention might reduce cognitive decline or dementia risk.

So where does this leave us? I recommend treating hearing loss regardless of what future research shows about dementia prevention. Here's why: Hearing loss affects your current quality of life, your social engagement, your safety (through fall risk), and your day-to-day cognitive function right now. These are real, measurable impacts that matter independent of long-term dementia risk.

If future research proves that hearing treatment also reduces dementia risk, that's an additional benefit. But even if it doesn't, treating hearing loss is still worthwhile for all the other ways it improves health and function. To learn more about how modern hearing aids work and what properly fitted devices can do, see my comprehensive guide on How Hearing Aids Work.

Beyond Cognition: Other Health Impacts of Untreated Hearing Loss

While much attention focuses on the hearing-dementia connection, hearing loss affects health and wellbeing in numerous other ways. Understanding these broader impacts helps explain why I consider hearing loss a whole-health issue, not just an ear problem.

Is Hearing Loss Associated with Depression and Mental Health?

Hearing loss is associated with significantly higher rates of depression and anxiety in adults. Multiple studies have found higher rates of depression and anxiety among people with hearing loss compared to those with normal hearing. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 24 cohort studies found that hearing loss is associated with a 1.35-fold increased risk of depression. The association appears to increase with severity of hearing loss.

Several mechanisms likely contribute to this relationship. Communication difficulty creates frustration and embarrassment. Social withdrawal—whether from avoiding difficult listening situations or feeling excluded from conversations—leads to isolation and loneliness. Both are strong risk factors for depression. The constant cognitive effort required for communication creates mental exhaustion. And hearing loss can affect sense of competence and independence, contributing to low mood and anxiety.

Importantly, the relationship appears to be bidirectional. Depression can affect how people experience and cope with hearing loss. It may make them less likely to seek treatment or less successful in adapting to hearing aids. Some research suggests that treating hearing loss may help improve mood, though more studies are needed to establish this definitively.

I want to emphasize that depression in people with hearing loss is not inevitable or "understandable given the circumstances." It's a real mental health condition that deserves evaluation and treatment. If you're experiencing symptoms of depression—persistent low mood, loss of interest in activities, changes in sleep or appetite, feelings of hopelessness—please talk to your physician. Depression is treatable. Addressing both hearing loss and mood can work together to improve quality of life.

Why Does Hearing Loss Increase Fall Risk?

I discussed the balance mechanism earlier, but the fall risk associated with hearing loss deserves special attention because of its serious health consequences. Falls are not just a minor inconvenience for older adults. They can be life-changing or even life-threatening events.

Research by Lin and colleagues found that adults aged 40-69 with even mild hearing loss (25 dB hearing level or greater) were nearly three times more likely to have a history of falling compared to those with normal hearing. Each 10 dB increase in hearing loss was associated with approximately 1.4-fold increase in odds of falling.

Another study by Viljanen and colleagues followed older adults and found that those with hearing impairment had a significantly increased risk of falls over a three-year period. The risk remained significant even after accounting for other fall risk factors like age, chronic conditions, and medication use.

Why does this matter so much? Falls in older adults frequently result in fractures, particularly hip fractures. These carry substantial morbidity and mortality. Even falls that don't cause fractures can lead to decreased mobility, fear of falling that limits activities, and loss of independence. Falls are a leading cause of injury-related hospitalizations and deaths among older adults.

There's emerging evidence that treating hearing loss might help reduce fall risk, though more research is needed to confirm this. The proposed mechanism is that hearing aids reduce cognitive load and improve spatial awareness. This frees up cognitive resources for balance and gait control. Some studies have found that hearing aid users have better postural stability during cognitive dual-task situations.

CLINICIAN'S NOTE: I frequently hear from patients who mention balance concerns or a history of falls. Many haven't connected these issues to their hearing loss. When I explain the relationship, it often motivates them to address their hearing more seriously. One of my patients recently told me that after getting hearing aids, she felt more confident walking. She stopped holding onto walls in her house. She hadn't even realized she had been doing it.

How Is Cardiovascular Health Related to Hearing Loss?

The relationship between cardiovascular health and hearing loss has received increasing attention in recent years. There's good evidence that cardiovascular risk factors—including hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and high cholesterol—are associated with increased risk of hearing loss.

The proposed mechanism involves blood flow. The inner ear requires adequate blood supply to function properly. The hair cells that detect sound are among the most metabolically active cells in the body. They're vulnerable to reduced blood flow or oxygen delivery. Conditions that affect small blood vessels throughout the body, like diabetes and hypertension, can damage these delicate structures.

Research has shown that people with two or more cardiovascular risk factors have significantly increased odds of hearing loss compared to those without these risk factors. Among older adults, conditions like coronary artery disease, diabetes, and hypertension are all associated with worse hearing and accelerated hearing loss over time.

This creates an interesting possibility: hearing loss might serve as an early biomarker for cardiovascular disease. Some research has suggested that hearing changes might appear before other signs of vascular disease become apparent. While we're not ready to use hearing tests as cardiovascular screening tools, the association highlights the interconnection between sensory health and overall physical health.

The relationship works in reverse as well. Managing cardiovascular risk factors—controlling blood pressure, managing diabetes, not smoking, maintaining healthy cholesterol levels—may help protect hearing as we age. This is one reason why comprehensive hearing evaluation should include assessment of general health status and cardiovascular risk factors.

There's also evidence connecting hearing loss to increased risk of hospitalizations and healthcare utilization. People with untreated hearing loss have higher rates of emergency department visits and hospital admissions. Over a 10-year period, individuals with untreated hearing loss incurred an average of $22,434 more in healthcare costs than those without hearing loss, experienced about 50% more hospital stays, and were 17% more likely to have an emergency department visit. The mechanisms aren't entirely clear but may involve communication difficulties in healthcare settings, reduced ability to follow medical instructions, and the effects of social isolation on overall health.

How Does Hearing Loss Affect Quality of Life and Relationships?

Beyond the measurable health outcomes, hearing loss profoundly affects quality of life in ways that matter deeply to people but don't always show up in medical studies. I see this every day through the stories patients and families share.

Communication is fundamental to human connection. When hearing difficulty interferes with conversation, it doesn't just affect information exchange. It affects intimacy, understanding, and the quality of relationships. Spouses describe feeling disconnected from partners who can't hear them. Adult children worry about their parents' withdrawal. Friends drift apart when conversation becomes too difficult.

The strain on relationships is real and measurable. Studies have found that hearing loss is associated with decreased relationship satisfaction for both the person with hearing loss and their communication partners. Research has shown that a significant percentage of people with hearing loss report that their condition has negatively affected relationships with partners, family, and friends. Partners of people with untreated hearing loss report feelings of frustration, isolation, and sadness about the loss of easy communication.

There's also impact on work performance and career. Even if hearing loss doesn't prevent someone from doing their job tasks, communication difficulty can affect participation in meetings, relationships with colleagues, and confidence in professional settings. Some people with untreated hearing loss limit their career advancement or retire earlier than they otherwise would.

The effects extend to leisure and recreation. People stop going to movies, theater performances, or concerts. They avoid restaurants and social gatherings. They give up activities that used to bring joy because the listening effort makes them too challenging or tiring.

CLINICIAN'S NOTE: Some of the most rewarding moments come when patients return for follow-up visits after successfully adapting to hearing aids. They tell stories about having real conversations with grandchildren. Understanding their spouse without asking them to repeat. Attending a concert and actually enjoying it. These aren't abstract health outcomes. They're the things that make life meaningful. And often, family members will call or email to thank me because they got their loved one back.

Who Is Most at Risk?

Understanding risk factors for hearing loss—and consequently, for the cognitive and health impacts associated with hearing loss—can help with early detection and prevention. Let's look at the major risk categories.

Does Age Increase Hearing Loss Risk?

Age-related hearing loss, called presbycusis, is extremely common. The prevalence increases dramatically with age. Studies suggest that approximately one-quarter of adults in their sixties and nearly two-thirds of Americans aged seventy and older have hearing loss.

Presbycusis typically affects high-frequency hearing first. That's why the first sign is often difficulty understanding speech in noisy environments. High-frequency consonants carry much of speech clarity. The hearing loss is usually gradual and bilateral, affecting both ears symmetrically.

What causes age-related hearing loss? It's likely multifactorial. Cumulative noise exposure over a lifetime plays a role. Changes in inner ear structures and blood supply contribute. Genetic factors matter. Effects of other medical conditions add up. There's no way to completely prevent presbycusis. But managing other risk factors and protecting hearing from excessive noise throughout life may help minimize age-related changes.

The connection to cognitive health is particularly important in older adults because this is also when dementia risk increases. The question of whether treating age-related hearing loss might help preserve cognitive function is exactly what studies like ACHIEVE are investigating.

One crucial point: Don't assume that hearing loss is inevitable or untreatable just because you're getting older. Age-related hearing loss responds well to treatment with properly fitted hearing aids. And given what we know about the potential cognitive and health impacts of untreated hearing loss, addressing presbycusis may be more important than ever.

Does Noise Exposure Cause Hearing Loss?

Noise-induced hearing loss is entirely preventable but extremely common. Excessive noise exposure damages the delicate hair cells in the inner ear. Unlike many tissues in the body, these hair cells don't regenerate in humans. Once damaged, they're permanently lost.

Both occupational and recreational noise can cause hearing loss. Occupational noise exposure in industries like construction, manufacturing, military service, and agriculture accounts for significant hearing loss. Recreational noise from activities like shooting sports, motorcycling, loud music concerts, or prolonged use of personal listening devices also contributes substantially to hearing loss, particularly in younger adults.

The concern with noise-induced hearing loss is that it often develops in younger people. This potentially extends the duration of hearing loss over a lifetime. Someone who develops significant hearing loss at 40 or 50 faces decades of potential cognitive load, social challenges, and health impacts unless the hearing loss is treated.

This makes noise prevention crucial across the lifespan. Protecting your hearing with appropriate ear protection in noisy environments is important. Limiting exposure to loud sounds matters. Keeping volume moderate on personal listening devices is essential. All are important preventive measures.

If you have history of significant noise exposure, getting a baseline hearing test and monitoring for changes is important. Early detection allows for earlier intervention if hearing loss develops.

What Other Medical Conditions Affect Hearing?

Several medical conditions and exposures increase risk of hearing loss beyond age and noise. Understanding these can help with both prevention and early detection.

Diabetes is associated with increased risk of hearing loss, likely through effects on small blood vessels and nerves in the inner ear. Research suggests that hearing loss is approximately twice as common in people with diabetes compared to those without diabetes. Good diabetes management may help protect hearing.

Cardiovascular disease and risk factors (hypertension, high cholesterol, smoking) are associated with hearing loss, again likely through vascular mechanisms. Maintaining cardiovascular health appears to support hearing health as well.

Certain medications are ototoxic—they can damage hearing. The most concerning are some chemotherapy agents (particularly platinum-based drugs like cisplatin), high doses of aspirin, and certain antibiotics (particularly aminoglycosides). If you're taking any medications and notice hearing changes, consult your physician and audiologist.

Genetic factors play a role in both age-related and noise-induced hearing loss susceptibility. Some people are more vulnerable to hearing loss from age or noise exposure due to genetic variations. Family history of early hearing loss may suggest increased genetic risk.

Head trauma can cause hearing loss either through direct damage to inner ear structures or through damage to the auditory nerve. This is one reason why hearing evaluation is often part of assessment after significant head injury.

CLINICIAN'S NOTE: When I conduct new patient evaluations, I always take a comprehensive history. Noise exposure. Medical conditions. Family history. Medications. This helps me understand not just current hearing status but risk factors for progression. For patients with multiple risk factors—say, diabetes plus significant past noise exposure—I'm especially likely to recommend regular monitoring even if current hearing is still good. Early intervention may be particularly important.

The Case for Early Intervention

Given everything we've discussed about how hearing loss affects the brain, cognition, balance, social engagement, and overall health, the question becomes: When should you address hearing loss? The evidence increasingly points toward earlier rather than later.

Why Does Waiting Make Things Harder?

There's a common pattern I see. Someone notices hearing difficulty but decides to wait. "It's not that bad yet," they say. "I'll get hearing aids when I really need them." Then years go by. When they finally come in for evaluation, they often have moderate to severe hearing loss. They struggle more with hearing aid adjustment than if they had come in earlier.

Why does waiting make things harder? Several reasons, all related to the brain changes we discussed earlier.

First, auditory deprivation becomes more entrenched. The longer your brain goes without clear auditory input, the more it reorganizes. When you finally get hearing aids, your brain has to relearn how to process sound efficiently. This adaptation period can take weeks to months. For people with many years of untreated hearing loss, some aspects of auditory processing may never fully recover to what they would have been with earlier intervention.

Second, social habits form. If you've spent years avoiding noisy restaurants, declining invitations to group events, and limiting social interaction, these patterns can persist even after hearing improves. Reengaging socially requires effort. It often works better if you haven't completely withdrawn from social activity.

Third, the cumulative cognitive load over years of untreated hearing loss may have effects that aren't immediately reversible with treatment. While many people report feeling mentally sharper after getting hearing aids, we don't know if the years of increased cognitive effort have long-term consequences that treating the hearing loss can't completely reverse.

Fourth, speech understanding in complex situations may be more difficult to restore. Even with excellent hearing aids, people with long-term hearing loss often continue to struggle in some situations more than they might have if hearing loss had been addressed earlier. Like understanding rapid speech or following conversation in very noisy environments.

None of this means it's ever "too late" to address hearing loss. I have patients in their 80s and 90s who get substantial benefit from hearing aids. But the evidence suggests that earlier intervention—treating hearing loss when it's mild rather than waiting until it's severe—offers advantages for both current function and potentially long-term outcomes.

For more on this topic, including why people sometimes struggle even with technically normal hearing tests, see my post on Why You Still Struggle to Hear Even When Your Hearing Test Is Normal.

What Does "Early Intervention" Actually Mean?

When I talk about early intervention, what exactly do I mean? It's worth clarifying because there's often confusion about when hearing loss is "significant enough" to treat.

Traditional medical practice suggested waiting to treat hearing loss until it reached moderate severity. The reasoning was that hearing aids were expensive, had limitations, and adjustment could be challenging. So treatment should be reserved for when hearing loss was substantial enough to clearly justify it.

That approach is changing for several reasons. First, hearing aids have improved dramatically in terms of sound quality, features, and ease of use. Second, we understand more about brain plasticity and auditory deprivation. This suggests earlier treatment may be better for preserving auditory processing abilities. Third, growing awareness of the cognitive and health impacts of untreated hearing loss provides additional motivation for earlier treatment.

Current thinking is that hearing loss should be considered for treatment when it begins to affect function or quality of life, even if it's still technically mild. If you're starting to struggle in restaurants or meetings, missing parts of conversations, asking people to repeat frequently, or feeling mentally fatigued after social events, that's significant enough to consider treatment.

Early intervention also means establishing baseline hearing even before loss is apparent. For adults over 50, I recommend getting a baseline hearing test even if you're not noticing problems. This provides comparison for future tests. It allows monitoring for changes. Early detection means earlier treatment if hearing loss develops.

It's also worth noting that "treatment" doesn't always mean hearing aids immediately. For very mild loss, sometimes addressing specific communication situations with assistive listening devices or communication strategies is sufficient. For mild loss where aids aren't yet needed full-time, some people start by using them selectively in challenging situations. The key is active management rather than ignoring the problem until it becomes severe.

Why Should You Treat Hearing Loss Early?

While hearing aids are the primary treatment for most hearing loss, a comprehensive approach to managing hearing difficulty and supporting cognitive health involves multiple strategies.

Communication strategies matter. This includes things like positioning yourself to see the speaker's face. Visual cues support understanding. Reduce background noise when possible. Ask speakers to get your attention before speaking. Use specific rather than generic repair strategies. Say "Could you repeat the last part?" rather than just "What?"

Environmental modifications can help. Better lighting for lipreading. Reduce echo with soft furnishings. Use visual alerts for doorbell or phone. Arrange furniture to facilitate conversation. All support communication. For people with hearing loss, small environmental changes can have disproportionate impact on function.

Assistive technology beyond hearing aids includes devices like captioned telephones, TV listening systems, and alerting devices. Newer technologies like smartphone apps for transcription and remote microphone systems that connect to hearing aids expand options considerably.

Cognitive stimulation through activities, learning, social engagement, and mental challenges may support brain health independent of hearing. While we can't say that cognitive training prevents dementia, staying mentally active is part of a comprehensive brain health approach.

It's also worth considering how hearing loss and tinnitus often co-occur. Many people with hearing loss also experience tinnitus (ringing or other sounds in the ears). Addressing both together often provides better outcomes than treating one in isolation. For more information on this connection, see my article on Can Hearing Aids Help My Tinnitus.

CLINICIAN'S NOTE: My approach with new patients always includes comprehensive evaluation. Not just measuring hearing loss, but understanding how it affects their daily life. What situations are most challenging. What goals they have. What other factors might be relevant. Then we develop a treatment plan that might include hearing aids, but also communication counseling, assistive device recommendations, tinnitus management if needed, and ongoing monitoring. The most successful outcomes come from this comprehensive, individualized approach rather than just dispensing hearing aids and hoping for the best.

What to Do If You're Concerned

If you're concerned about hearing loss—your own or a family member's—and its potential effects on cognitive health, what concrete steps should you take? Let me walk you through the process.

How Do You Get a Proper Hearing Evaluation?

Comprehensive hearing evaluation goes well beyond just testing whether you can hear beeps at different pitches. Here's what thorough evaluation should include.

The basic audiogram measures pure-tone hearing sensitivity across different frequencies in each ear. This establishes the degree and pattern of hearing loss. But it's just the starting point.

Speech testing is crucial. This includes measuring how well you understand words at comfortable volume levels and in the presence of background noise. Two people can have identical audiograms but very different speech understanding abilities. This significantly affects real-world function and treatment planning.

Cognitive screening is offered when clinically relevant—particularly for adults where brain health is a concern. We use the Cognivue assessment to establish baseline cognitive function. This screening is not a diagnosis. It helps us understand how hearing loss may be affecting cognitive performance and identifies when more detailed medical evaluation may be appropriate. If significant concerns are identified, we coordinate with your primary care physician or recommend referral to a neurologist for comprehensive assessment.

Otoscopic examination checks your ear canals and eardrums for problems like wax buildup, infection, or structural abnormalities. These might affect hearing or require medical treatment before considering hearing aids.

Case history is equally important as the testing itself. A good audiologist will ask detailed questions. When you first noticed hearing difficulty. What situations are most challenging. Whether you have tinnitus. Your noise exposure history. Medical history. Family history. Medications. What your communication needs and goals are.

Additional testing might include tympanometry (measuring middle ear function), acoustic reflex testing, or otoacoustic emissions testing depending on the clinical picture. If hearing loss is asymmetric or accompanied by other symptoms, I may recommend medical evaluation or imaging.

Real Ear Measurement, which I'll discuss more in the treatment section, is essential if hearing aids are recommended. Research and surveys suggest that somewhere between roughly a third to under half of audiologists routinely perform this verification, though it's considered best practice. But it's crucial for ensuring hearing aids are providing the right amount of amplification. I won't fit hearing aids without it.

Questions to ask your audiologist during evaluation include:

- What type of hearing loss do I have, and what likely caused it?

- How does my speech understanding compare to what would be expected for this degree of hearing loss?

- Am I a candidate for hearing aids, and what would realistic expectations be?

- Do you use Real Ear Measurement to verify hearing aid fitting?

- What follow-up and ongoing care is included?

How Do You Understand Your Hearing Test Results?

Interpreting hearing test results can be confusing. Let me clarify some common questions and misconceptions.

First, hearing loss is categorized by degree: normal (0-25 dB), mild (26-40 dB), moderate (41-55 dB), moderately severe (56-70 dB), severe (71-90 dB), and profound (>90 dB). These categories help with general communication but don't tell the whole story. Two people with mild hearing loss might have very different functional impact depending on the specific frequency pattern and their speech understanding.

High-frequency hearing loss is the most common pattern, especially in age-related and noise-induced loss. This particularly affects understanding of consonant sounds and makes speech understanding in noise difficult. You might hear that someone is talking but not understand what they're saying. This is characteristic of high-frequency loss.

One of the most frustrating situations for patients is when they struggle to understand speech but their hearing test looks "normal" or nearly normal. This can happen for several reasons. First, standard audiograms test quiet pure tones, not the complex task of understanding speech in noise. Second, some people have hidden hearing loss—damage to nerve fibers that doesn't show up on standard testing but affects function. Third, early cognitive changes can affect ability to process complex auditory information even when hearing sensitivity is normal.

If you're in this situation—struggling functionally but told your hearing is normal—don't accept "there's nothing wrong" as an answer. Ask about speech-in-noise testing. Consider evaluation by an audiologist who specializes in complex cases. Don't hesitate to pursue cognitive screening if concerns persist.

Regarding when hearing loss is "significant enough" to treat: There's no absolute threshold. The question is whether hearing loss is affecting your function, quality of life, social engagement, or safety. If the answer is yes, it's significant enough to consider treatment, even if it's technically mild.

What Are the Treatment Options and Realistic Expectations?

For most people with sensorineural hearing loss (the most common type), hearing aids are the primary treatment option. Modern hearing aids are sophisticated devices. They can significantly improve hearing and quality of life when properly fitted.

I want to emphasize "properly fitted." There's huge variability in hearing aid outcomes. Much of it comes down to fitting quality. This is where Real Ear Measurement becomes critical. This is an objective verification procedure. A thin probe microphone measures sound levels in your ear canal while you're wearing hearing aids. It ensures the devices are providing appropriate amplification across frequencies according to your specific hearing loss.

Unfortunately, research and surveys suggest that somewhere between roughly a third to under half of hearing aid fittings include Real Ear Measurement, though this is considered best practice by major audiology organizations. This is one of the biggest factors affecting why some people do very well with hearing aids while others struggle or give up.

At our practice, Real Ear Measurement is standard for every fitting. I won't verify hearing aids any other way because I can't ensure appropriate outcomes without it. If you're considering hearing aids, ask whether Real Ear Measurement will be performed. If not, consider finding a different provider.

Beyond proper fitting, success with hearing aids depends on several factors. First, appropriate expectations. Hearing aids will not restore hearing to "normal" or allow you to hear perfectly in every situation. They can significantly improve communication and reduce listening effort. But there will still be challenging situations. Understanding this from the start helps prevent disappointment.

Second, allowing adequate adjustment time. Your brain needs time to adapt to amplified sound, especially if you've had hearing loss for years. Initial reactions—that sounds are too loud, voices sound strange, or aids are uncomfortable—often improve substantially over weeks as your brain adapts. Many people who struggle initially become very satisfied users if they stick with the adjustment process.

Third, follow-up care. Hearing aids require fine-tuning, adjustments, maintenance, and updates over time. A good provider relationship with ongoing care is essential for long-term success.

What about hearing aids and cognition? As I discussed earlier, we can't promise that hearing aids prevent dementia. What we can say is that hearing aids reduce cognitive load. They improve speech understanding. They support social engagement. They may reduce fall risk. These effects on daily cognitive function and quality of life are valuable independent of any potential long-term dementia risk reduction.

For detailed information about hearing aid technology, types, features, and what to expect, see my comprehensive guide on How Hearing Aids Work.

CLINICIAN'S NOTE: I tell patients that adjusting to hearing aids is a process, not an event. The first fitting is the beginning, not the end. We'll work together over several appointments to optimize settings. Address any concerns. Help your brain adapt to amplification. The patients who do best are those who commit to this process. Wear their aids consistently. Communicate openly about challenges so we can address them. That partnership is what leads to successful outcomes.

How Do You Address Cognitive Concerns Alongside Hearing?

If you have both hearing concerns and cognitive concerns—or family members are worried about your memory or thinking alongside your hearing—it's important to address both appropriately.

Start by getting comprehensive hearing evaluation as described above. Make sure the audiologist knows about cognitive concerns so they can be factored into assessment and treatment planning. We can offer baseline cognitive screening when clinically relevant to help identify when more detailed evaluation may be needed.

If cognitive concerns are significant—memory problems interfering with daily activities, getting lost in familiar places, difficulty managing finances or medications, confusion, or personality changes—discuss these with your primary care physician. They may recommend more comprehensive cognitive assessment or referral to a neurologist or geriatrician.

It's important to coordinate care between specialists. Your audiologist should know about cognitive issues because they affect hearing aid fitting strategy and expectations. Your physician should know about hearing loss because it's relevant to overall health assessment and may affect medical communication.

Be aware that hearing loss can affect performance on some cognitive screening tests. If you're being tested for cognitive function, make sure you're wearing hearing aids or other accommodations are made so you can actually hear the test instructions and questions. Some apparent cognitive impairment is actually hearing difficulty.

Managing hearing loss is part of a comprehensive approach to brain health, but not the only part. Other important factors include:

- Physical activity and exercise

- Social engagement and meaningful relationships

- Mental stimulation and continued learning

- Management of cardiovascular risk factors

- Healthy diet

- Adequate sleep

- Management of depression or anxiety

- Avoiding excessive alcohol and not smoking

Think of hearing treatment as one important element in overall brain health strategy, working alongside these other factors. We can't prevent all cognitive decline. But optimizing modifiable risk factors—including hearing—gives you the best chance for maintaining cognitive function as you age.

If You're Worried About Memory: The Simplest Next Step

Here's what to do if you're concerned about both hearing and cognition:

1. Get a comprehensive hearing evaluation with speech-in-noise testing

Don't settle for just a basic hearing test. Make sure speech understanding in realistic listening conditions is assessed.

2. Treat hearing loss if it's impacting your daily function

Don't wait until it's "bad enough." If you're struggling in conversations, missing information, or feeling mentally exhausted from listening effort, that's significant enough to address.

3. Use cognitive screening as a baseline

We offer screening to establish where you are now. This isn't a diagnosis—it's a tool to help identify when medical follow-up may be appropriate.

4. Coordinate with your primary care physician or neurologist if red flags exist

If screening raises concerns or you're experiencing memory problems beyond what hearing difficulty would explain, get proper medical evaluation.

The key is not to assume that cognitive difficulties are "just" hearing loss or "just" aging. Get both evaluated properly so you and your healthcare team can develop an appropriate plan.

What Researchers Agree On vs What's Still Being Studied

Understanding where the science is solid versus where questions remain helps you make informed decisions.

High Confidence (Strong Consensus)

✓ Hearing loss is associated with increased cognitive load during listening tasks

✓ Hearing loss is associated with higher risk of social withdrawal and isolation

✓ Hearing loss significantly increases fall risk, even after controlling for other factors

✓ Cardiovascular risk factors are associated with increased risk of hearing loss

✓ Untreated hearing loss is associated with higher healthcare utilization and costs

Still Being Actively Studied (Questions Remain)

? Whether treating hearing loss prevents or delays dementia for most people

? Who benefits most from early hearing intervention for cognitive health

? How early intervention needs to happen to maximize potential brain health benefits

? What specific mechanisms account for the hearing-cognition connection (likely multiple)

? Whether the relationship is primarily causal, or partly due to common underlying factors

This balanced view aligns with how the Lancet Commission and other major scientific bodies approach the topic. We have strong evidence of important associations. We're still clarifying the extent to which these relationships are causal and modifiable through treatment.

Common Myths About Hearing Loss and Cognition

Myth #1: "Hearing loss is just a normal part of aging—nothing you can do about it"

Reality: While age-related hearing loss is common, it's highly treatable with properly fitted hearing aids. And given the connections to cognitive health, fall risk, and quality of life, addressing it matters more than ever.

Myth #2: "If my hearing test is normal, my hearing is fine"

Reality: Standard hearing tests don't capture all aspects of auditory function. Some people struggle with speech-in-noise understanding or auditory processing even with "normal" audiograms.

Myth #3: "Hearing aids will restore my hearing to normal"

Reality: Hearing aids significantly improve communication and reduce listening effort, but they don't restore hearing to how it was before hearing loss. Realistic expectations lead to better outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can hearing aids prevent dementia?

We don't have definitive proof yet. The ACHIEVE trial (published in 2023) didn't find a significant effect in the overall study population. However, there was a promising finding in a higher-risk subgroup showing 48% reduction in cognitive decline over three years. Several other trials are ongoing.

What we can say is that hearing aids reduce cognitive load, improve social engagement, and support daily cognitive function in measurable ways. Even if future research doesn't prove dementia prevention, these immediate benefits on quality of life and current cognitive function make treating hearing loss worthwhile.

At what point does hearing loss start affecting cognitive function?

Research suggests that even mild hearing loss is associated with increased cognitive load during listening tasks. Studies have shown that people with mild hearing loss may have accelerated cognitive decline compared to those with normal hearing, though individual variation is substantial.

The functional impact depends not just on degree of loss but on factors like the speech understanding difficulty you experience. How much you're straining to understand conversation. Whether you're withdrawing from social activities because of hearing challenges. If hearing difficulty is affecting your daily function or social engagement, it's worth addressing regardless of whether it's classified as "mild."

I passed my hearing test but still struggle to understand people—could this affect my brain?

Yes, this is possible and increasingly recognized. Several situations can cause this disconnect between test results and functional difficulty:

- Hidden hearing loss—damage to auditory nerve fibers that doesn't show up on standard testing but affects ability to understand speech in noise

- Early auditory processing issues that affect complex speech understanding even when pure tone hearing is normal

- Very early cognitive changes affecting auditory processing

- Testing environment differs from real-world listening challenges

If you're struggling functionally despite normal test results, ask about speech-in-noise testing. Consider evaluation by an audiologist who specializes in complex cases. Don't hesitate to pursue cognitive screening if concerns persist. Your functional experience matters more than test results showing "normal." For more on this, see my detailed post on Why You Still Struggle to Hear Even When Your Hearing Test Is Normal.

Is it too late to help my cognition if I've had hearing loss for years?

It's never too late to get benefit from treating hearing loss, though earlier intervention appears to offer advantages. Research suggests that the brain can adapt to amplification even after years of untreated hearing loss. However, the adjustment period may be longer. Some aspects of auditory processing might not fully recover to what they would have been with earlier treatment.

Many patients who've had hearing loss for years report feeling mentally clearer, less fatigued, and more engaged socially after successfully adjusting to hearing aids. While we can't reverse years of auditory deprivation, we can improve current function and quality of life at any age.

Does tinnitus affect cognitive function the same way hearing loss does?

Tinnitus (ringing or other sounds in the ears) and hearing loss often occur together. Both can affect cognitive function through somewhat different mechanisms.

Tinnitus can increase cognitive load by creating distraction and interfering with concentration. It's associated with higher rates of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance. All of these can affect cognitive function. Some research suggests that severe, bothersome tinnitus is associated with cognitive difficulties even independent of hearing loss.

The good news is that treating hearing loss often helps tinnitus. Many people find that their tinnitus is less noticeable or bothersome when wearing properly fitted hearing aids. For more information on this connection, see my article on Can Hearing Aids Help My Tinnitus.

How long does it take for the brain to adjust to hearing aids?

The adjustment period varies significantly between individuals. Most people notice substantial improvement in comfort and benefit within 3-4 weeks of consistent hearing aid use. However, full adjustment—where your brain has optimally adapted to processing amplified sound—can take several months.

Factors affecting adjustment time include:

- Duration of untreated hearing loss (longer often means longer adjustment)

- Degree of hearing loss

- Age (younger people often adapt faster, but successful adaptation happens at all ages)

- Consistency of hearing aid use (wearing aids full-time helps brain adapt faster)

- Quality of fitting (properly fitted aids with Real Ear Measurement verification make adjustment easier)

It's important to work closely with your audiologist during this period. Don't give up if initial experiences are challenging. Most adjustment difficulties can be resolved with appropriate follow-up care and fine-tuning.

Will my memory improve if I start wearing hearing aids?

This is a nuanced question requiring an honest answer. Hearing aids will likely improve your functional cognitive performance in daily life by reducing listening effort and mental fatigue. Many patients report feeling mentally sharper, less exhausted after social activities, and better able to participate in conversations and remember what was discussed.

However, hearing aids are unlikely to "cure" memory problems or reverse existing cognitive decline. If you have memory difficulties that extend beyond situations related to mishearing information, hearing aids alone won't solve those problems.

What hearing aids can do is remove one barrier to cognitive function. If you're currently using mental resources just to figure out what people are saying, hearing aids free up those resources for actually processing and remembering information. That's valuable, but it's different from improving underlying memory capacity.

Should I get hearing aids even if my hearing loss is mild?

This depends on how the hearing loss affects you functionally. The question isn't just "What does my audiogram show?" but "Is hearing difficulty affecting my quality of life, social engagement, work performance, or safety?"

If you're struggling in restaurants or meetings, asking people to repeat frequently, feeling mentally fatigued after conversations, or starting to avoid social situations because of hearing difficulty, that's significant functional impact. Even if the hearing loss is technically mild.

Given what we know about cognitive load, auditory deprivation, and social isolation, there's a reasonable case for addressing hearing loss early rather than waiting until it becomes severe. Modern hearing aids are quite sophisticated and can help even with mild loss when properly fitted.

That said, not everyone with mild loss needs immediate hearing aid intervention. Sometimes communication strategies, assistive listening devices for specific situations, or monitoring with plans to intervene if loss progresses are appropriate approaches. This is a discussion to have with an audiologist who can assess both your hearing and your functional needs.

Can hearing loss cause balance problems and falls?

Yes, there's substantial evidence that hearing loss is associated with increased fall risk. Research shows that even mild hearing loss increases fall risk nearly threefold. Risk increases further with severity of hearing loss.

The mechanisms include reduced spatial awareness from lack of auditory environmental cues, increased cognitive load affecting resources available for balance control, and potentially shared underlying pathology affecting both hearing and vestibular (balance) systems in the inner ear.

This connection is important because falls in older adults can have serious consequences including fractures, hospitalization, and loss of independence. Some research suggests that treating hearing loss might help reduce fall risk, though more studies are needed to confirm this. At minimum, being aware of increased fall risk allows for appropriate precautions.

Is hearing loss an early sign of dementia?

Hearing loss is not itself a sign of dementia. They are separate conditions, though research shows they're associated.

However, it's true that some very early cognitive changes can affect auditory processing even when hearing sensitivity is normal. And hearing loss can make cognitive problems more apparent because communication becomes more difficult.

If you or family members are concerned about both hearing and cognition, it's important to get proper evaluation of both. Make sure your audiologist knows about cognitive concerns. Make sure your physician knows about hearing difficulty. In some cases, what appears to be cognitive impairment is partially due to hearing difficulty interfering with communication and testing. In other cases, both conditions are present and both need appropriate management.

Related Topics

To deepen your understanding of hearing loss, brain health, and comprehensive care, I recommend exploring these related articles from my blog:

Better Hearing, Better Brain, Better Life

This article explores the connections between hearing health and overall brain function. It discusses how addressing hearing loss can support cognitive vitality and quality of life.

How Hearing Aids Work: A Comprehensive Guide

My complete pillar page on hearing aid technology, types, features, and what to expect from modern devices. Essential reading if you're considering hearing aids.

Why You Still Struggle to Hear Even When Your Hearing Test Is Normal

Many people experience functional hearing difficulty despite normal audiograms. This post explains the phenomenon, possible causes, and what to do about it.

Can Hearing Aids Help My Tinnitus?

Tinnitus often accompanies hearing loss and can affect cognitive function through distraction and stress. Learn about the connection and how treating hearing loss often helps tinnitus as well.

References & Key Studies

Major Research Reports:

- Livingston G, et al. (2024). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet. Full text

Hearing Loss and Dementia Risk:

- Lin FR, et al. (2011). Hearing loss and incident dementia. Archives of Neurology (now JAMA Neurology). PubMed

- Lin FR, et al. (2013). Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Internal Medicine. Full text

Intervention Studies:

- Lin FR, et al. (2023). Hearing intervention versus health education control to reduce cognitive decline in older adults with hearing loss in the USA (ACHIEVE): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. Full text

Cognitive Load and Effortful Listening:

- Pichora-Fuller MK, et al. (2016). Hearing impairment and cognitive energy: The Framework for Understanding Effortful Listening (FUEL). Ear and Hearing. Full text

Auditory Deprivation and Brain Reorganization:

- Brain morphological changes systematic review. Frontiers in Neuroscience. Full text

- Campbell & Sharma 2014: Cross-modal reorganization in mild-moderate hearing loss. PMC

- Kral 2023: Comprehensive review on crossmodal plasticity. Trends in Neurosciences. Full text

- Glick & Sharma 2020: Hearing aids can reverse cross-modal reorganization. Frontiers in Neuroscience. Full text

Falls and Balance:

- Lin FR, Ferrucci L. (2012). Hearing loss and falls among older adults in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine. Full text

- Falls prevention systematic review. PubMed

- Hearing aids and fall risk. Full text

- Viljanen A, et al. (2009). Hearing as a predictor of falls and postural balance in older female twins. Journals of Gerontology Series A. PubMed

Mental Health:

- Meta-analysis on hearing loss and depression. PubMed

- Hearing loss and anxiety in older adults. Full text

Social Isolation:

Cardiovascular Health:

- Cardiovascular risk factors and hearing loss. Full text

Diabetes and Hearing Loss:

- Diabetes and hearing loss meta-analysis. PubMed

Healthcare Utilization:

Real Ear Measurement:

- Real Ear Measurement importance. Full text

- REM adoption rates study. PubMed

- Hearing aid benefit verification. Full text

Brain Plasticity and Age:

- Brain plasticity and age. Full text

About Timpanogos Hearing & Tinnitus

I'm Dr. Layne Garrett, Au.D., FAAA, ABAC, CH-TM, CDP, founder of Timpanogos Hearing & Tinnitus. I've specialized in hearing loss and tinnitus treatment for over 20 years. Our practices are in American Fork and Spanish Fork, Utah.

My approach is built on evidence-based care, comprehensive evaluation, and Real Ear Measurement verification for every hearing aid fitting. We track outcomes and focus on measurable improvements in communication, quality of life, and—for tinnitus patients—reductions in distress, improved sleep, better concentration, and enhanced daily function.

I believe in transparency and education. I want every patient to understand their hearing loss. The treatment options available. Realistic expectations. How hearing health connects to overall brain and physical health. My goal isn't just to fit hearing aids. It's to help you maintain communication, social engagement, safety, and quality of life throughout your lifetime.

If you're concerned about hearing loss and its potential effects on cognition, balance, or overall health, I invite you to schedule a comprehensive evaluation. We'll thoroughly assess your hearing with speech-in-noise testing. We can offer baseline cognitive screening when clinically relevant. We'll discuss how hearing loss is affecting your daily life. Review all your options. Develop a personalized treatment plan that addresses your unique needs and goals.

Reviewed/Edited By

Modified /Edited by: Dr. Layne Garrett, Au.D., FAAA, ABAC, CH-TM, CDP

Date: February 5, 2026 at 9:00 AM